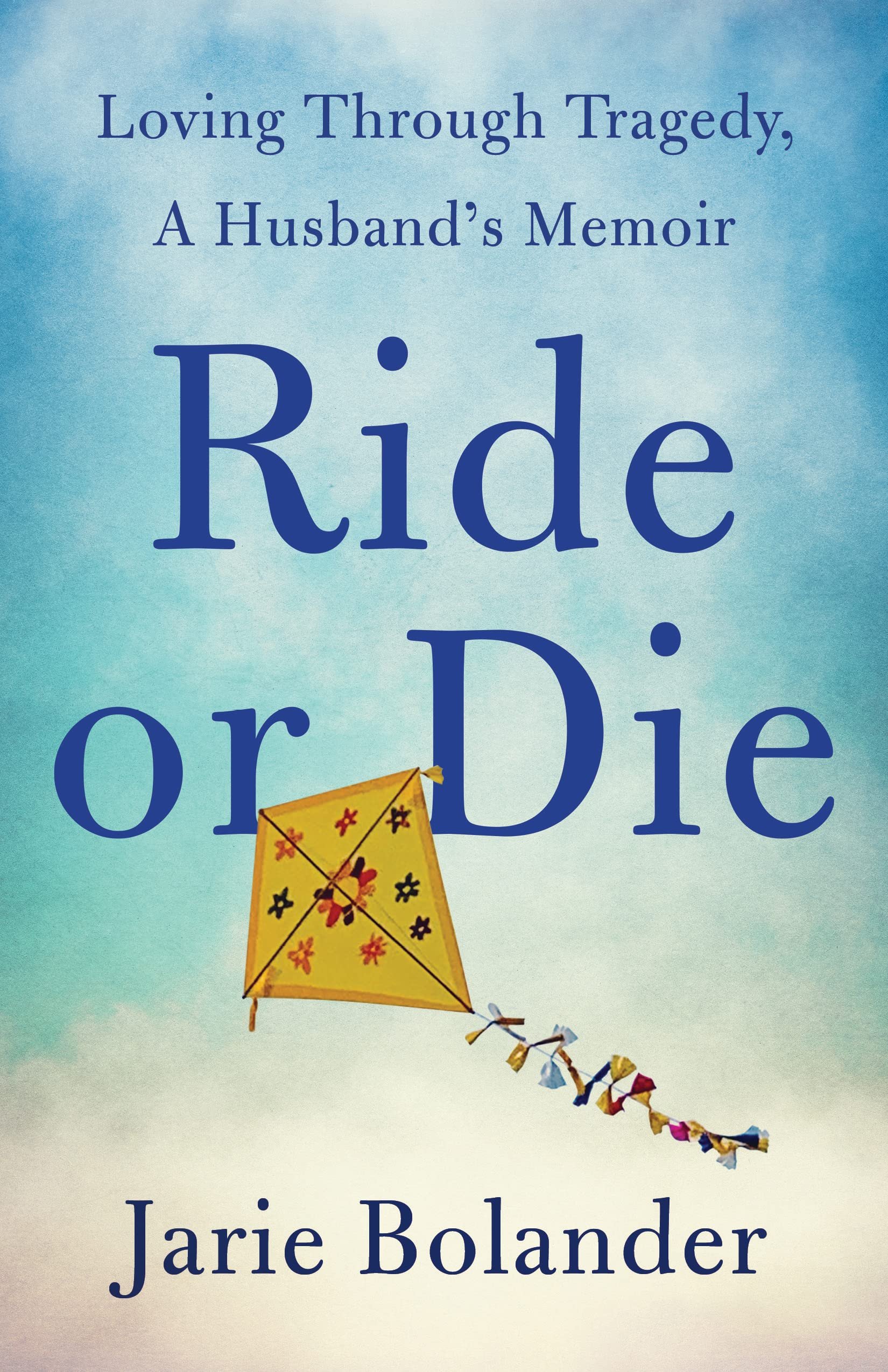

By: Jarie Bolander

I have a confession to make.

I cried when my wife Jane died of leukemia on April 3rd, 2017.

Uncontrollable sobs. Running nose. Watering eyes. A full and complete meltdown.

I did this after the fire department came to pronounce her dead, the coroner came to certify that there was no foul play, they zipped her up in a body bag, wheeled her down the two flights of narrow stairs on a ratty old purble gurney, my in-laws and brother-in-law left, and I was alone in our apartment.

Alone with the grief of realizing that I would never talk to her again.

Never kiss her.

Never hear her laugh.

I waited to ball my eyes out because I was taught to suck it up.

Walk it off.

It’s just a scratch.

Boys (Men) don’t cry.

Thus began my journey into understanding my grief over Jane dying, how to express it, and more importantly, how to talk about it.

How to Express the Emotions You Feel

Crying, like laughing, expresses your inner feelings to the rest of the world. Unlike laughing, which is acceptable for anyone to do, crying has a stigma for men that’s rooted deep into our culture and is making men both sick and distraught.

For men, well most men, the expression of a vulnerable emotion, one that exposes your weaknesses, is more frightening than the dumps of cortisol that slowly eat at your insides. Some even find it so unpalatable that they would rather take their own life than deal with it.

The Complex Emotions of Grief Brought About by Trauma

In his book, The Body Keeps the Score, Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, explains how our bodies react to and absorb trauma. This accumulation of trauma leads to all sorts of physical and mental abnormalities that create a cycle that is hard to break out of.

Coupling that with an unwillingness to express a natural emotion, at the time it’s occurring, makes it even more difficult for men to release the tensions that get locked down deep inside.

“Being able to feel safe with other people is probably the single most important aspect of mental health; safe connections are fundamental to meaningful and satisfying lives,” says Dr. van der Kolk.

It’s this challenge of feeling safe to express oneself that men struggle with and society reinforces.

This gets even worse when dealing with a stressful, traumatic situation where you have to make life or death decisions all while trying to suppress your grief so you can give the impression that you have your act together.

Some Perspective

Let’s step back a bit and take a more pragmatic view of grief and the expectations that society has on men.

One of the best phrases I like to use to encapsulate the general view of grief is

It’s okay for women to cry but not get angry.

It’s okay for men to get angry but not cry.

This view seems to encapsulate the problem since both anger and crying are emotions all humans can (and must) express yet the stereotype that men should not show their grief stems from society's expectations that men remain stoic in the face of challenging times. Men’s job is to protect the tribe from aggression and to be ever vigilant.

This responsibility does not lend itself to being vulnerable and expressing grief.

Some Hope

I do have some hope that attitudes will change, not from general society but from the military, who recognize the fact that 22 service members commit suicide every day.

Most of those suicides are men that have lost their support network and can’t express the grief and sorrow over the loss of meaning and direction in their life. This is similar to the challenges that many men face nowadays in a world that continues to stratify towards accomplishment and less towards being valuable as a human being.

Some Actions

Grief comes in many different forms. The grief I’m most familiar with is over the death of a spouse.

What’s tricky about death is that society does not handle it well. In the US, we’re all about the happy ending, everything is Instagram awesome, and I can handle anything.

This is blatantly wrong.

What I have found is that when most folks deal with a grieving man, they tend to get stuck in an empathy loop that freezes them into platitudes like “sorry for your loss” or my favorite “Anything I can do to help?”

In order to escape the empathy loop, we should try to rapidly move to compassion so you can take action to engage in the uncomfortable, messy, and difficult work of processing grief.

Here are a few things that I have found that help me and those around me process grief.

Get past platitudes and take action. Simple things like “I’m going to the store, need anything?” Or “I’m trying a new restaurant, want to come?”

Ask a specific question about the dead person like their name, favorite food, what they loved about them, etc.

Listen and don’t give advice unless asked. It’s tempting to want to help but listening is the best way to support someone.

Acknowledge that what happened was horrible. Don’t try and justify whatever happened.

Have a ritual that you can commit to. Like “I’ll call you next week” or “coffee in two weeks”, etc. If you can’t commit, don’t.

Small Things Matter

One last thing that’s important to remember is that the small things matter to a grieving man. There are no magic solutions or a single thing that will solve a man’s grief. Rather, it’s the little, consistent things that build over time. It’s the support that’s both present in the moment or the feeling that you’re not alone that makes a difference. It’s this connection to others and that someone cares about you is what all people, especially men, need while grieving and we as a society struggle to provide them.

Jarie Bolander caught the startup bug right after graduating from San Jose State University in 1995 with a degree in electrical engineering. With 6 startups, 7.75 books, and 10 patents under his belt, his experience runs the gamut from semiconductors to life sciences to nonprofits. He also hosts a podcast called The Entrepreneur Ethos, which is based on his last book by the same name. When he’s not helping clients convert a concept to a viable strategy, he can be found on the Jiu-Jitsu mat (he’s a blue belt), interviewing entrepreneurs on his podcast, or researching the latest in earthship construction techniques. He’s engaged to a wonderful woman named Minerva, her daughter, and their Bernedoodle, Sage. Currently, Jarie lives and works in San Francisco, where he works as head of market strategy for Decision Counsel, a B2B growth consulting firm.