Inspiration is a funny thing. It can come to us like a lightning bolt, through the lyrics of a song, or in the fog of a dream. Ask any writer where their stories come from and you’ll get a myriad of answers, and in that vein I created the WHAT (What the Hell Are you Thinking?) interview. Always including in the WHAT is one random question to really dig down into the interviewees mind, and probably supply some illumination into my own as well.

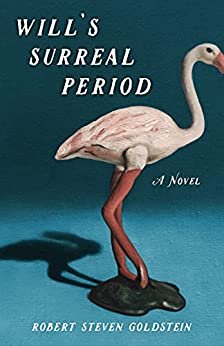

Today’s guest for the WHAT is Robert Steven Goldstein, a critically acclaimed author, taps into his childhood experiences with a dysfunctional family to interrogate the bond between loved ones and what it takes to mend broken relationships. Goldstein’s deep love for art and creativity is reflected in his vibrant cast of characters as they each find their own path to self-discovery, even if that means choosing themselves over family.

Ideas for our books can come from just about anywhere, and sometimes even we can’t pinpoint exactly how or why. Did you have a specific origin point for your book?

For my new novel Will’s Surreal Period, there was, indeed, a brief twinkle of inspiration. It stemmed from an article I read about a sculptor who had developed a unique style of work which was much admired—only to learn that the artistic style was actually the product of a life-threatening brain tumor. The only way for the artist to save his life was to have the tumor removed—but that would have meant sacrificing his art as well. According to the article, the artist had not yet made a decision about what to do.

Once the original concept existed, how did you build a plot around it?

That heart wrenching dilemma about the artist and the brain tumor was just the kernel of an idea. The story for Will’s Surreal Period now needed to be fleshed out, other characters with their own problems and paths needed to be dreamed up, and a real plot needed to be created. That’s the point for me where the twinkle of inspiration gives way to some real work. I don’t know how other writers do it—I suppose some mark up index cards, or make copious notes, or create some verbal equivalent of a storyboard. I must confess, though, that I don’t do anything quite so concrete. I just go into a sort of writer’s trance and ponder obsessively for a week or two—sometimes sitting around, sometimes hiking with my dog, sometimes showering or shaving or eating, and even sometimes when I’m ostensibly focusing on something that I really need to (like a conversation with my wife about an upcoming social engagement—in which case it never takes her long to figure out that my mind is someplace else). My internal process for the story always starts with the characters. When a few of those have finally materialized, relatively firmly in my mind, I then work through the barest outline of a plot. That’s really all I need to start writing.

Have you ever had the plot firmly in place, only to find it changing as the story moved from your mind to paper?

I actually never have the plot firmly in place! I think if I did, I’d find the act of writing tedious. For me, the pleasure of writing is figuring it out as I go, letting the last incident I dreamed up lead to another and another. Some years ago, I wrote a novel that had a bit of a murder mystery in it, and I honestly didn’t know who did it or how it would be resolved until I got there. I suppose there are spirited pros and cons to such an approach, but for me, one very good thing was that it kept me as curious and engaged along the way as I hoped my readers would be.

Do story ideas come to you often, or is fresh material hard to come by?

Big ideas, those that can actually serve as the kernel for a new book, don’t come to me often at all. But little ideas—what will happen next in the story, what new character might suddenly pop up in this chapter, what unexpected twists do I now envision down the road—those manifest constantly, but only when I’m actively writing.

How do you choose which story to write next, if you’ve got more than one percolating?

It’s hard enough for me to get one good idea for a book percolating. Which is probably for the best, because novels take a good while to churn out—there’s a relatively finite number of them that I’m going to wind up producing in my life—so the kernel of an idea for a book becomes a very important decision. The fact that I rarely have more than one at my disposal at any given time is probably a blessing—no need to agonize over which to pick—and no torturous second-guessing, months later, that I’ve been toiling over the wrong idea for the past two hundred pages.

I have 6 cats and a Dalmatian (seriously, check my Instagram feed) and I usually have at least one or two snuggling with me when I write. Do you have a writing buddy, or do you find it distracting?

My big old dog Cali, a ten-year-old Akita Inu and Blue Heeler mix, is sprawled out on the couch in my office at this very moment, watching intently as I type. I think she somehow realizes that although there is no dog in Will’s Surreal Period—two of the main characters do own a cat…