Today's guest is Lyn Liao Butler, author of The Tiger Mom's Tale and the upcoming Red Thread of Fate. Lyn joined me today to talk about the experience of debuting during the pandemic, how having an active lifestyle helps with her writing and mind / body balance, as well as how important research is when writing in a specific setting.

Putting the Main Character’s Sexual and Gender Identity in the Reader’s Hands

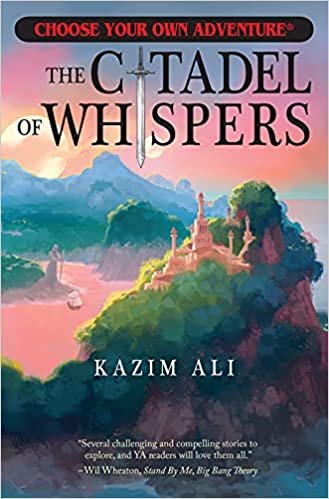

By Kazim Ali

Making Krishi, the main character of my new Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book, The Citadel of Whispers, a gender-neutral character was never supposed to be a big deal. In the classic line of books, the protagonist characters—the character the reader assumed the persona of—was always written as gender neutral. It was the marketing and art departments of the original publisher that had to make decisions about what the cover would look like and what the internal art would look like. It was felt at the time that though girls might read a book with a boy protagonist the reverse might not be true. While most of those early books depicted a boy in the cover art and internal art, the text itself never really gendered the character by either behavior, appearance, or in the action of the text.

It was a short leap from that concept to the notion that characters themselves in the book might have various relationships to gender. Not only did I carefully construct the main character, Krishi, as someone who could either be identified as a boy, a girl, or gender neutral, but other characters in the book also have different relationships to classic gender stereotypes and to fantasy stereotypes as well. For example, Krishi’s two main friends have abilities different that one might expect. Zara, a girl, is the best fighter in the school but is also upset at having to cut her long hair to conform to the gender-neutral appearance that all Whisperers are expected to have in order to be better spies. Saeed, a small boy, is often thought of as physically weak but at several points in the story he manages to defeat fighters bigger and stronger than him by his cunning.

Tough independent girls appeared many times before in children’s literature of course, but it was probably Sally Kimball, created by Donald J. Sobol as part of his Encyclopedia Brown series, who was the first real bruiser. She was 10 years but often bested larger boys, often giving 14-year-old Bugs Meany an actual black eye to match the metaphorical black eye he got when Encyclopedia exposed his role in various petty crimes. Sally wasn’t a well-rounded hero. She was the muscle to Encyclopedia’s fey, retiring brains. It’s interesting to note that the not-quite-feminist icon Buffy Summers of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was also not overly noted for their intelligence. The first round of girl action heroes could be as buff and butch as the boys but she couldn’t have it all.

The Whisperers in The Citadel of Whispers, know that in their work they have to be able to pass as anything. The book actually opens with a martial arts class in which the students—boys and girls and everyone else—have to engage in combat while corseted into restrictive dresses. Their normal clothes are gender neutral tunics and pants, and their hair must be uniformly shoulder length, neither longer nor shorter. Other characters in the book also defy gender expectations. The combat teacher is an athletic woman, while the dance instructor is a slim man; the rogue-like pirate ship captain (think the Han Solo-type) is a sixty-something year old woman with a penchant for taking swigs out of a flask and smoking tobacco from a long pipe.

Since fantasy is a genre with such historic tropes (around both race and gender), I knew I couldn’t write a story with the same figures. Princess Leia of Star Wars is a warrior woman for sure (I once heard that if you calculate the ratio of shots fired to successful hits, Leia is the best shot of all the characters in the series), but her primary attribute in the original trilogy still leaned into the traditional role of damsel in distress in need of rescue. It wasn’t until the sequel trilogy that the world around her had evolved enough for her to be fully depicted at what was only winked at in a few scenes of the original: she was the political and military leader of the resistance.

I also wanted to work against the norm of most fantasy milieux: a pseudo medieval European context in terms of the castles, the costumes, the social roles. Rather than Tolkien or Lewis (or Brooks or Eddings, who drew from those two), I drew instead upon the wonderful Amar Chitra Katha comics of my childhood, describing Indian architecture and giving most—but not all—the characters Indian names. Innovation is also a firm tradition in speculative fiction. When Anne McCaffrey created her world of the dragonriders of Pern with the first novel in 1968, she created a matriarchal political structure in which homosexuality was an ordinary part of life. The characters who disapproved of it were seen is reactionary and out of touch and were almost always villainous in the context of the story.

Like Krishi, most characters in The Citadel of Whispers, have their own relationship to gender, some more traditional—like Sandhya, the martial arts instructor, or Etheldreda, a gardener with big plans—and others, like the master Whisperer Shivani or the sullen new student Arjun, each disrupt expectations a reader might have. There are trans characters, revealed as such in the text, and others might be read that way. There is at least one character who is written as a drag performer, but is not revealed that way in the text. Hey, I have to save something for Book 2!

In the end, the point was not to be “political” about gender but to be inclusive. The point was to write a book that any boy or girl could read and not feel excluded from, more importantly any young person who had a complicated relationship to their own gender, or wasn’t sure what it meant to them, could read this book as well and feel that they had a home in it. An imagined world ought to include everyone with an imagination.

KAZIM ALI is an award-winning LGBTQ+ author and the Chair of the Department of Literature at the University of California, San Diego. His new book The Citadel of Whispers,, is available now. Learn more on his website kazimali.com

How Not To Lose Your Mojo For Writing When Rejection Is Rampant

You have squeezed out every drop of heart and soul. You’ve fleshed out intriguing characters, worked and reworked the plot points, and studied every sentence until your eyes crossed. Your critique partners have praised your progress, and the editing software has ranked your manuscript right up there with Jennifer Weiner. This is your time to shine.

With a solid query letter and the required pages, you hit send. And wait. The following writing days have you switching from your WIP to your inbox, hitting refresh, and dreaming of publishing success. Unfortunately, for a great majority of writers, initial responses are disappointing.

Since I began my Writing Table podcast, I have asked over fifty guests about their publishing journeys. For most, it’s as rocky as a hike up Kilimanjaro. For a few, their talent and patience paid off, and they landed agents instantly. Author Laurie Frankel spent three months polishing the query letter she sent to the singular agent who would sign her. Frankel’s experience is uncommon, a testament to the time she spent refining her message.

For most of us, the landscape looks quite different. We slug through countless rejections, combing them for meaning, and if we hone our craft and polish our manuscripts enough, we receive requests for pages. What happens then is anyone’s guess, as there are no guarantees of anything in this business. Before you allow rejections to crush your writing soul, let’s study what they mean. Since dashing off my first query in the fall of 2015, I have received at least one-hundred rejections which fall into one of three categories:

· Immediate rejections

o We will not be pursuing representation of your manuscript

o Because of the high volume of queries I receive, I will only be responding to authors where I will be asking for more materials. If you do not hear from me, consider it a “no.”

o Unfortunately, I'm afraid the project isn't the right fit for me.

· Considered, but ultimately rejected

o Thank you very much for your query, which we have read with interest. Unfortunately, the project does not seem right for this agency, and we are sorry that we cannot offer to serve as your literary agent.

o Unfortunately, after careful consideration of your manuscript, we have determined that it does not fit our needs.

o I'm afraid I didn't fall in love with it as I had hoped I would.

· Closely considered, rejected with feedback: Rare commentary provided by time-strapped agents who recognize the diamond in the rough.

o Thanks for sending me your heartfelt novel. I like the idea but I had a hard time with the characters. You're good with dialogue - but there's too much of it. It all sounds pretty natural but it's not all necessary. I didn't get caught up in the story. I'm sorry to not have a more positive response but I appreciate the chance and wish you the best on your search.

o Sorry, but I’m taking a final pass on your work. As a suggestion, you could consolidate your first forty or so pages to avoid repetition.

o There's some cleaning up to do, but it's nothing developmental, and just picking and choosing the best way to word things to fit the characters.

Agents don’t take pleasure in rejections. There are exponentially more authors than agents, and even fewer editors poised to purchase your manuscript. This reality presents an unreal workload for agents as they screen for projects to champion. It’s not personal. An agent might enjoy reading a manuscript, but if they don’t think they can sell it, they won’t sign you. It’s that simple.

How to stay motivated when rejections come?

· Expand your writing community through Twitter, Facebook groups, writing conferences and workshops. Writing is a solitary job, and it’s easy to feel isolated. Know you’re not alone. The writing community is especially supportive of its own, so don’t be afraid to reach out via social media. Some of my best writing pals came into my life this way, and I might have quit a long time ago if not for their support. Writing organizations and NANOWRIMO (National Novel Writing Month) introduce authors through message boards and local programming.

· Don’t stop writing. If your butt doesn’t land in that chair, you have nothing to edit.

· When making significant changes to a manuscript, use the “save as” feature to preserve the former version. You never know when you might want to resuscitate a discarded character or scene.

· Rejections sting, but underneath the discomfort lies relevant feedback. Let the initial pain wear off, then search for helpful nuggets. The line you love might distract the reader from the core of the story, or a character doesn’t move the plot forward. An agent might recommend a developmental edit or only a few tweaks. Actionable feedback from an agent can be solid gold.

· Author Camille Pagan reminds newbie authors to ask, “What would a career author do?” Face writing as if you were already the career author you hope to become. Get up and write regularly. You’re never too good to stop refining your craft. Listen to feedback. Trust your gut. Don’t give up.

Kris Clink is the author of Goodbye, Lark Lovejoy and Sissie Klein is Completely Normal, which have received praise from Bustle, Midwest Book Review, Kirkus Reviews, Women.com, Lone Star Literary, Brit + Co, Travel and Leisure Magazine, and Entertainment Weekly. Set in middle America, her novels are laced with love, heartbreak, and just enough snark to rock the boat for the relatable characters as they confront transformative challenges. She is the host of Kris Clink’s Writing Table, a podcast about books and writing, where she interviews a variety of publishing professionals and authors from Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) to Camille Pagán.